“The Closer They Come To Being Finished The More Compromised They Become”: An Interview with Duncan Fegredo

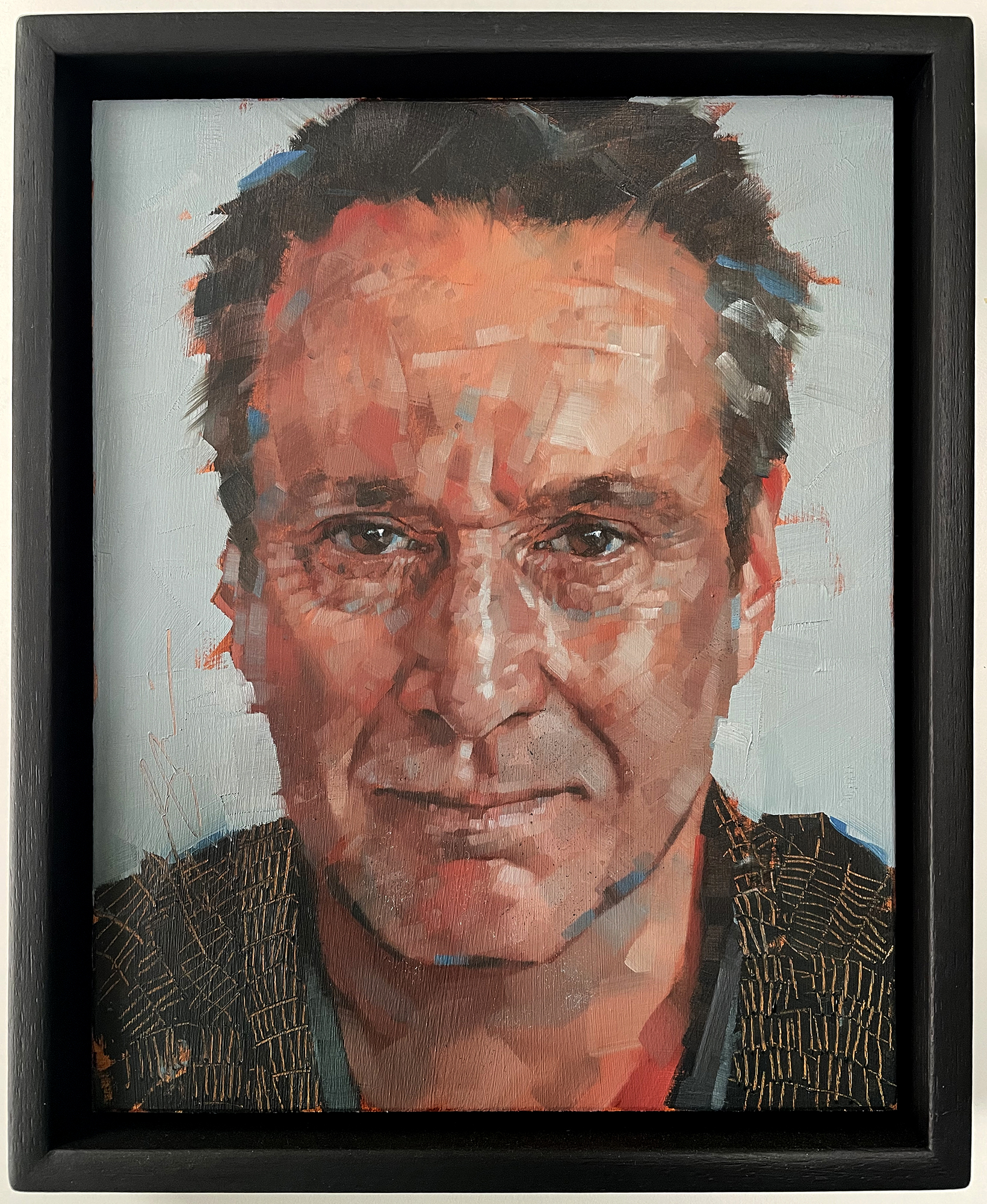

Duncan Fegredo, painting by Simon Davis.

Duncan Fegredo, painting by Simon Davis.

Duncan Fegredo’s career ranges from being one of the defining Vertigo artists, to the infamous British magazine Crisis, to the killer of Hellboy. His collaborations with Peter Milligan are legendary. From Enigma, to Girl, to Face to, one of the all-time great Spider-Man stories, “Flowers for Rhino”, the two crafted beautifully told stories with unique voices, each of which had its own style and approach. Enigma in particular remains a brilliant work three decades after it was published: a look at sexuality and repression, superheroes and fantasy, with a "Definitive Edition" published by Berger Books, an imprint of Dark Horse, last year.

His other great collaboration is with Mike Mignola, for whom Fegredo drew multiple Hellboy miniseries: Darkness Calls, The Wild Hunt, and The Storm and The Fury. These served the epic conclusion of Hellboy’s saga, ending with the character's death. Drawn years ago when relatively few other artists had drawn Hellboy, Fegredo managed to put his own mark on the character. Since then, Mignola, Fegredo and Dave Stewart have collaborated on the short graphic novel The Midnight Circus, which marked a stylistic shift for Fegredo and featured some of his finest work.

Fegredo got his start working with Dave Thorpe on Heartbreak Hotel, drew comics for Crisis and 2000 AD, and went on to draw the Vertigo Kid Eternity miniseries written by Grant Morrison and Millennium Fever written by Nick Abadzis. For the then-upstart publisher Oni Press, Fegredo chronicled the escapades of New Jersey’s two greatest stoners, Jay & Silent Bob, written by Kevin Smith. Over the years he’s been a prolific cover artist, working on everything from Star Wars to Shade, the Changing Man and Aliens . He’s contributed to anthologies including Weird War Tales, Flinch, Dark Horse Presents and drawn issues of Tom Strong, House of Secrets and X-Force. More recently he illustrated and co-created MPH with Mark Millar.

Fegredo and I exchanged e-mails to talk about his work and career, a disastrous project at Marvel, and why he loves detailed artwork but finds his finished work dissatisfying.

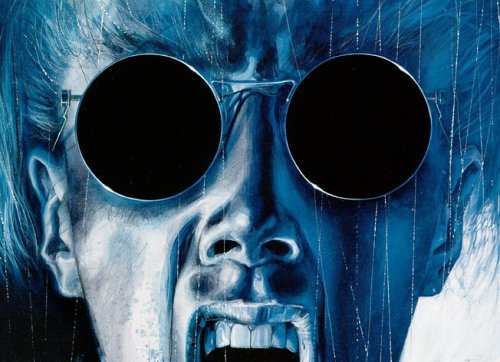

Fegredo's Joker illustration for the VS System trading card game.

Fegredo's Joker illustration for the VS System trading card game.

ALEX DUEBEN: What comics were you reading as a kid? What things in general obsessed you and made you go, I want to be an artist?

DUNCAN FEGREDO: As I kid I read any comics I could get my hands on. For the most part that meant British humor comics, simply because that was what was available. I suspect they were mostly passed on to us, we didn’t have a lot of money to spend on such things. Stuff like The Beano, The Dandy, Beezer, some boys adventure stuff like The Hotspur. The little pocket money I had went on Whizzer and Chips. Later there was a Disney comic, that was probably when I started copying the drawings, when I first made a connection to how these things were made, not that I thought of it that way at the time. This is the very early '70s, I was born in 1964. My elder brother had a friend who lent us Power Comics, they reprinted Marvel Comics before Marvel had an official foothold in the UK with The Mighty World of Marvel in 1972. I was hooked pretty early, I’d buy a lot of the British reprint books. The real hook came with Star Wars, I was obsessed. I think at that point I drifted away from US reprints, I wanted science fiction and 2000 AD fit the bill perfectly. So first I wanted to work for Disney, then Marvel, then 2000 AD. I mean, I wanted to be a spaceman first but asthma made that unlikely. Little did I realize that being a sickly loner child set me up better for obsessing over drawing and comics.

What’s your background? Did you study art?

I always drew. I realized it was something I could do better than the other kids, even when very young. I wasn’t the most gregarious child, I found it more comfortable to be on my own, drawing, so I just improved by the simple fact of solitude. Later, when it came to study, my mum would say, that’s great, but concentrate on the more academic subjects. Which I did, rather half-heartedly.

Eventually I did what I always wanted, took a degree in graphic design at Leeds Polytechnic, with the intention of specializing in illustration. On paper the prospectus looked great, it suggested the course would touch on animation, science fiction illustration, film, etc. Which I suppose is true if you had the focus to do it all yourself. The reality was rather different. This was 1984, computers were not unknown, except at Leeds Poly where countless hours were wasted making us visualize typography by hand. It was a dead skill, which pretty much summed up much of the course. The one good thing about attending Leeds was meeting my now-wife, Diana. I couldn’t have gotten through the intervening years without her support.

I coasted along for a year and finally reconnected with comics in my second year. The only comic I continued to read at that point was 2000 AD. I chanced across a copy of Daredevil on a news rack, picked it up, flipped through, put it back. I returned the next day and repeated the process. It was the "Pariah" issue of the Born Again story line [Daredevil #229, April 1986], and it bothered me. Mostly I really disliked the cover, but I couldn’t stop looking at it. I purchased it, read it repeatedly, pored over those almost crude yet so naturalistic drawings. A new comic shop had also opened in Leeds, something I’d never really had access too. Most of that second year was a bit aimless, just the loosest desire to draw comics. I also spent a lot of time going out sketching in shopping centers, on the street, trying to improve my figure drawing. I don’t think I did any life drawing at all in my three years at the Poly but these self-motivated drawing sessions gave me a real grounding that has informed everything I’ve done since. I mean, they were horrible drawings but the act of observing and trying to make a record of folk sitting, drinking, doing life stuff really stuck. My tutors weren’t much impressed by my apparent lack of progress so a few projects were suggested for my final year, I chose to illustrate John Milton’s Paradise Lost.

Was this around the time you met Dave Thorpe?

During the summer of ’86 I return home and commenced deciphering the Milton tome. It was uphill work, but rich with imagery. Satan's fall from heaven, demonic councils in hell, a cast worthy of any overwrought comic. I scribbled away and hit up the idea of drawing them all as biomechanic creatures. Or something, I don’t know why. I was still overly fond of H.R. Giger and that kind of got entangled with my liking of Ralph Steadman. I was also reading more comics, a friend lent me his run of Warrior comics and turned me on to Watchmen. In my mind Paradise Lost and comics were becoming entangled. Just before my final year at Leeds commenced I travel down to London with that friend to attend the UK Comic Art Convention; it was and remains the best convention I ever attended. It blew my mind. Real artists who drew real comics, everywhere. And accessible. Up until this point I knew artists drew comics, but the how and why it could be possible was unknown. But here were real artists I could talk to and watch as they sketched for fans. It was just wonderful.

I had prepared for the convention by putting a small portfolio together. Mostly work in progress stats of my Paradise Lost work, fiery robots in hell. I may have had the only four pages of comics I had drawn at that point as well, large-scale pages drawn in a sub-Gilbert Shelton underground style. I’d drawn them the previous years, the result of a piece drawn for Martin Salisbury, a first-year tutor and the only one to share any interest in or encouragement for comics. But I’d already moved on from there, so probably not. So I showed the art to any artist willing to look, if the moment felt right, but mostly I observed. I recall meeting Brendan McCarthy in his wonderful exhibition of Artoons, he took a look at my folio and said I could ink him anytime. He was being kind of course, but his work in 2000 AD was a big influence on me. His figure work in the opening chapter alone of Sooner or Later–written by Peter Milligan–along with Ian Gibson’s work on Halo Jones really impressed on me the importance of body language.

Late on the last day I was perusing the publisher tables. I didn’t really know anything about Escape, but publisher–and nowadays historian–Paul Gravett was on the stand and was happy to take samples of my work. Some time after I had returned to Leeds I received a very enthusiastic letter from Dave Thorpe. Dave’s Doc Chaos comic was published by Escape, Paul had passed along my samples and piqued Dave’s interest, and so we corresponded during the year I finished my degree. The plan was for Dave to reboot Doc Chaos with me on the art. It was slow going. I never really got the strip, I wasn’t remotely on the same wavelength. That and I still hadn’t really drawn any pages. I don’t think I got more than 15 or so pages drawn, they were terrible.

So your entrance into comics is yet another story of Paul Gravett connecting people and projects?

I wasn’t really aware of that at the time. I’m not sure I was even aware of Escape magazine at the time, but then for a college student I was woefully unaware of more mainstream-style magazines as well. It was only a year or so later that style bibles like The Face and i-D Magazine would start to feature comic articles about Watchmen and The Dark Knight Returns. There’s no doubt that Paul’s interest in my work started a domino effect.

Your first published work was a strip that Thorpe wrote, "Repossession Blues", in Heartbreak Hotel, is that right?

My first published comic, yes, but not my first published work. I had drew a series of illustrations for Interzone magazine. When the Watchmen signing tour passed through Leeds, I went along with my folio and got talking to organizer Mike Lake - along with Nick Landau, who was one of the founders of Forbidden Planet and Titan Books. He thought my Paradise Lost stuff would be good for Dragon’s Dream. Of course I utterly failed to follow up on this as I just thought he was being nice. There is a theme here, isn’t there? Anyway, one of the editors of Interzone was watching all this and introduced himself, he was in need of artists for the magazine and by an a remarkable coincidence lived about a five-minute walk from me.

"Repossession Blues" was the only comics work I completed with Dave. I never even got paid for it, but it served me well as a calling card. It was raw and muddled, not all my fault, but the sheer scale of a tabloid sized comic had impact.

You also did some illustrations for Thorpe's Doc Chaos, is that right?

The comic pages were never completed, never saw the light of day, but they were highly referenced by the artist who drew the book that finally saw print. Other than that I made one illustration for Dave’s Doc Chaos novella, The Chernobyl Effect. (I recall sitting next to Brett Ewins [at a signing for the book], though my absence in these pictures suggests a bathroom break!)

How did you end up filling in for Jim Baikie and drawing New Statesmen in Crisis?

The way I remember it, I received two phone calls in September of 1988, around two weeks apart. The first was from Karen Berger offering my a three-book prestige series called Kid Eternity. I don’t recall any other details, but I accepted - and obviously went into a blind panic because I still had no idea of how to make a comic. It was worse than that, in my mind "prestige book" meant it had to be painted like the Black Orchid series Dave McKean was making for DC. I’d spent the preceding years drawing scratchy, splatter black and white art, the idea of full-color painted art was just beyond me, but that’s what was happening because of a new and cheaper printing process. I was, and still am, red-green colorblind. Not to devastating effect, but enough to cause problems. It had always been a stumbling block.

Two weeks later I heard from Fleetway editor Steve MacManus regarding a couple of fill-in episodes of New Statesmen. Again, I said yes, I’d worry about the details later.

Now that I think about it I also heard from Steve Dillon, who was co-editor of Deadline magazine - would I like to illustrate some prose by Pete Milligan? Why yes, yes I would. Well, that never happened. Which is a shame as I would have been better suited to that over the comics work.

The reason all these offers came around the same time was because both "Repossession Blues" and samples of my Paradise Lost illustrations had been circulating in the Society of Strip Illustration, later known as the Comics Creators Guild. The work sparked interest in various quarters. Not that I knew at the time, I only ever attended one meeting, years later. My work got seen, connections made.

I figured I would do the New Statesmen work first, learn on the fly, and then apply that to the larger project that was Kid Eternity. Fortunately Karen was okay with this.

A few weeks later I had a meeting with Karen Berger at the Russell Hotel, just around the corner from the UK Comic Art Convention, or UKCAC as it was known. It was exciting but complicated by the fact I was staying with Dave Thorpe that weekend. He wasn’t particularly happy that I had all these offers of work and none of them included him in the picture. But he had a day job, working at Titan Books. He showed me a letter he’d sent to Karen trying to sell us as a team, I was less than happy about that as it was done without my knowledge. During a meal we both attended at the end of the con it became apparent that Dave, along the table from me, was sat next to Vortex Comics publisher/editor Bill Marks, selling him on the idea of publishing Doc Chaos. Without any previous discussion and knowing full well my interests lay elsewhere.

Of course I still had to learn to draw/paint and assemble a coherent page of comic art. Sigh.

Crisis was an interesting magazine with a lot of talented people. It only lasted a few years but what was it like? Did it feel like something exciting and different and new?

I was actually hoping to work for 2000 AD, I’d even sent pages of Paradise Lost and a couple of single page Judge Dredd strips to editor Steve MacManus. He was positive but regarding the Dredds he advised me to "lose them, not good.” I reacted poorly at the time, though of course he was right.

I didn’t really know what to make of Crisis at the time. It was rather more self-aware than I was, I’m afraid I was aware of the troubled world around me in the most passive way. I could see that Crisis could fill an editorial need, entertain but provide a viewpoint, food for thought. If only it hadn’t been so earnest. Deadline emerged around the same time, some people saw rivalry there, stupid really. It was definitely more hip, much more fun. I suspect if I’d worked there first, things would have developed very differently. I can’t imagine I would have tried to develop my work the same way.

You drew two New Statesman stories and then you also drew two Third World War stories, do I have that right?

Yes. On New Statesmen I attempted to work in a way that would fit in with Jim Baikie's style, line and wash. To say I struggled would be an understatement. In the second episode I tried to inject a little more spontaneity, an effort to cover up the obvious: I had no idea what I was doing. I changed my approach again when it came to Third World War, partly because I’d seen Simon Bisley’s Sláine pages at the Crisis launch party, they were just amazing to behold.

For Third World War you worked with Pat Mills. Did you have much interaction with him?

I’d spoken to Pat a few times before Crisis, only you don’t really talk to Pat, you listen. A lot. I don’t mean that as a criticism. He just had a lot of ideas and I think he called people to use them as sound boards, to siphon off his busy mind. His scripts were very precise, they would contain notes to reference the various cuttings from National Geographic he included. Very helpful.

You were also drawing covers for Crisis, a Third World War reprint, Judge Dredd Megazine in this period as well. Cover artwork is something you've done a lot over the years. How did you start?

They needed covers and they asked me, it was that simple. I had gained a degree more proficiency by that stage, simply by drawing and painting those four episodes in Crisis. The first Judge Dredd Megazine cover was art directed by Sean Phillips, he proved a marker pen sketch layout for me to work from.

And so you were doing all this while also working on Kid Eternity?

No, this was all, or mostly all before even starting Kid Eternity. I’m still amazed that Karen and DC were willing to wait for me all that time, but it was in their interest as there was no chance that I would’ve been able to draw Kid Eternity without that experience. It would have been a very different book.

Did you and Grant Morrison have much interaction while working on Kid Eternity? Did you know each other before?

Not really. We met a couple of times, but that was it. At the Crisis launch party I recall them telling an eye-opening tale of their experimentation with chaos magic. It involved a lot of masturbation and “Then the sun came out!” I think I called them once to ask about something in the first script but it was a bad line, I could barely make out their voice.

So when exactly did you start Kid Eternity? Did you feel ready?

It must have been somewhere around the end of 1988 or early ‘89. I know the whole thing took me a couple of years to paint and I recall reviewing the lettering placements in my hotel during San Diego Comic-Con in ‘91. I was there to promote Enigma and Touchmark [an abortive 'mature' comics imprint for Disney, for which Enigma was initially conceived]. I was surprised I was up for an Inkpot for my work on Kid Eternity. We all went to the pub instead. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

I’m not sure I would ever have felt I was ready, at that stage I was in a continuous state of trying to find a way to work that fit, that felt right to me. I was very susceptible to outside influences and during Kid Eternity that meant the work of Dave McKean. I was already very taken with Dave’s illustrative approach on Violent Cases, that only increased with Black Orchid and Arkham Asylum. I could see Dave was using a lot of photo ref and that made sense to me so I purchased a camcorder with the intention of filming myself and freeze framing to provide figure ref. It..

* This article was originally published here

Comments

Post a Comment